Mathematics Education (Signadou)

Teaching with Learning Objects:

Gifts from a Federal Santa Claus?

Between 2001 and 2006, State and Federal governments across both Australia and New Zealand are jointly involved in a collaborative venture to produce hundreds of high quality digital online resources for use across the years of schooling and across identified key learning areas of priority (including literacy for students at risk, mathematics and numeracy, science, LOTE and others). These Learning Objects are being produced by the Le@rning Federation, the public face of this collaboration, and are subject to strict criteria in terms of content, production quality and pedagogy (Atkins, 2003; The Le@rning Federation, 2004a ; The Le@rning Federation, 2004b).

"Specifically, learning objects are:

Digital 'pieces of learning material' of limited file size and number of interfaces that meet a learning objective;

Self-contained - each learning object can be used independently of other learning objects, or conversely, they can be aggregated - grouped together into larger collections of content to make a learning sequence;

Reusable - a single learning object may be used in multiple contexts for multiple purposes i.e. across disciplines and Key Learning Areas;

Tagged with metadata - for easy identification and referencing;

Easily accessible through world wide web repositories/databanks"

(Chapuis, 2003, 4-4)

Some years ago when computers were new to schools and we were seeking ways in which to best make use of them for teaching and learning, one memory that remains is that of disks full of small programs and games. Even before the days of online access to what now seems an infinite storehouse of possible resources, the number and range of software tools seemed almost overwhelming. In what ways, then, will hundreds of learning objects for schools be different to those early pioneers of technological pedagogy?

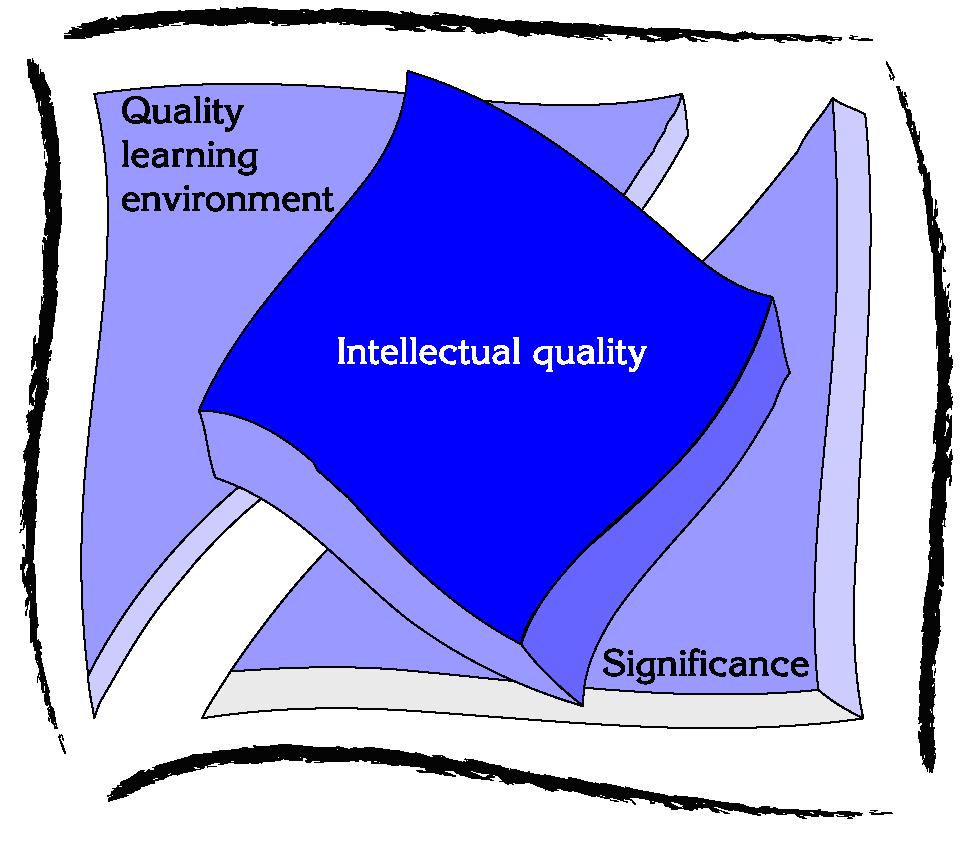

Two particular differences are significant. The quality of early (and current online) software was extremely variable. There was no consistency of interface, purpose or suitability. Whether developed by amateur teachers or by more sophisticated programmers, there were few marriages of subject knowledge with pedagogy. Learning Objects claim to offer such a marriage.

The second significant difference lies in the use of metadata. A greater problem than even variable quality lay in identifying and accessing what was available on the many disks full of software, and linking this to your classroom needs. Learning Objects are made to be interrogated. Inbuilt in each is carefully chosen information (metadata) which allows them to be searched across a range of criteria. While the prospect of hundreds (even thousands) of new teaching resources may inspire concern rather than joy for many, the ability to search and retrieve suitable resources for particular content areas, applications or pedagogical principles is extremely encouraging.

Room 206 Phone 02 62091142

Stephen Mark

ARNOLD

Stephen Mark

ARNOLD